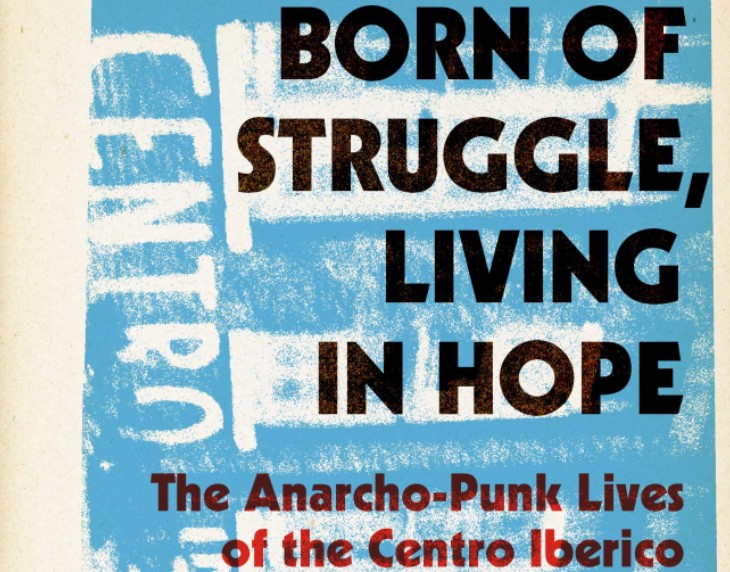

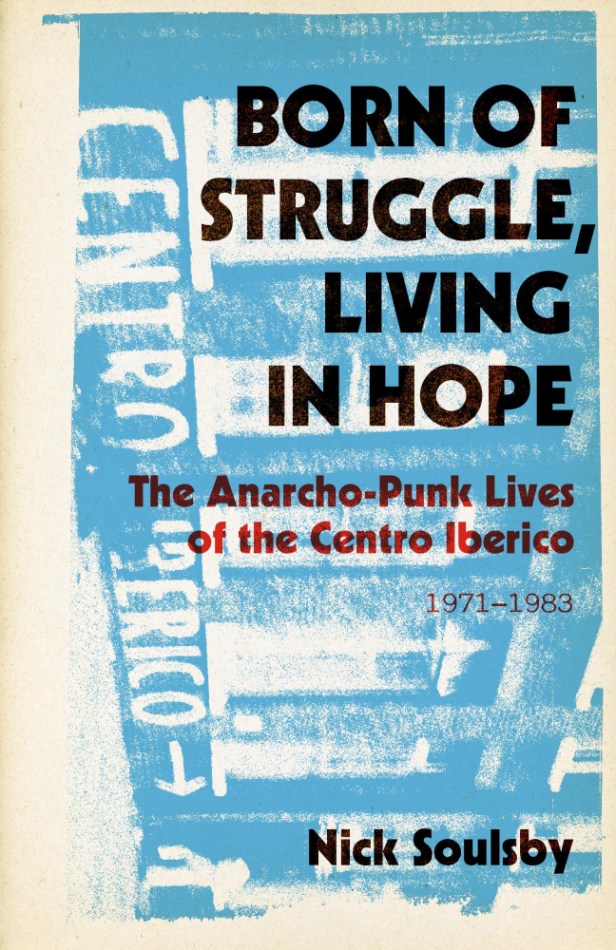

AUTHOR OF A new book on the ‘Anarcho-Punk Lives of the Centro Iberico, 1971-1983’, Nick Soulsby talks to The Hippies Now Wear Black about the research and writing of Born of Struggle, Living in Hope, the origins of the building as a base for anarchist émigrés from post-Civil War Spain, and the venue’s intersection with a new generation of eager young punks in the capital looking for new opportunties following the abrupt closure of the London Autonomy Centre in 1982.

For those not so familiar with Centro Iberico—as a London anarchist centre, organising hub and counter cultural venue—can you say a little about its history?

The story of Centro Iberico is a living link back through time. It’s a tale of a Spanish Civil War veteran condemned to death by Franco only to be exiled to London where he forged a new group to support his homeland; of mainland Britain’s only homegrown post-war ‘terrorist’ group and ongoing police skullduggery; of an entire abandoned school building taken over and protected by the people who got Joe Strummer’s 101ers into their house; of a community of industrious and talented young punks forging their own spaces in the city—first in the derelict docks of Wapping, then at the 421a Harrow Road schoolhouse… Oh, and William Orbit living in the old caretaker’s cottage too.

What led you to begin researching the book? What was the original inspiration?

Beginning in 2022, and for the next couple of years, I working on on creating a book on The New Blockaders (TNB), a rather extraordinary entity straddling anti-art, noise and absurdity from the early 1980s right through to the present day. TNB commenced in a shed in Northumberland with the album Changez Les Blockeurs, a wholly DIY LP of just 100 copies that now fetches over a thousand pounds, has been reissued in various formats over the years, and is a touchstone for the entirety of what became ‘noise music’.

Richard Rupenus, the prime instigator of TNB, who founded the group with his brother, Philip, was incredibly generous with information and connections—a total gentleman. Amidst the deluge of messages and memories, he told me he recalled performing at Centro Iberico, the squatted school in London. I didn’t doubt his memory at all—he has amazing recall—but I was puzzled. As far as I could tell, Centro Iberico closed in 1982, but TNB didn’t emerge until December of that year, and in those early days never played outside of Newcastle-Upon-Tyne’s Morden Tower. So how could he have played Centro Iberico?

I had heard the name ‘Centro Iberico’ over the years, it sort of ghosted through my reading and listening choices every now and again. But I had only the vaguest sense of why there would be an ‘Iberian Centre’ in London in the 1970s, or what it had to do with anarcho-punk in 1982.

So, attempting to answer my initial question related to Richard’s youthful activities, I ran into a further question: what was the Centro Iberico? In truth, I became hopelessly distracted from the book I was attempting to write—which will finally be emerging this summer on PC Press—so I took a deep breath, paused, and for a brief time focused wholly on attempting a comprehensive answer to the mystery of Centro Iberico.

Was PM Press the obvious publishers to pitch a project like this to? How receptive were they?

PM Press were extraordinary from day one: a near immediate ‘yes’, some sense of the parameters of what makes for a title they would look at — so I had something to shoot for — then the freedom to go ahead and make it happen.

I’d have to say I’ve been a reader of their titles on radical history—The Angry Brigade, Black Mask, the Red Army Faction, the George Jackson Brigade—for years, as well as appreciating Ian Glasper’s volumes on that post-punk and anarcho-punk moment—including The Day The Country Died, and Burning Britain. I think I did a little dance of delight when they so readily accepted that if I could do a good job, then they would take it. I had a substantial amount written already by the time I said ‘hi’ to them… It was all very smooth indeed.

How straightforward was it to unearth information about the venue? Dissident and counter cultural movements, especially those from an analogue age, often leave only the faintest of traces?

As a general philosophy, I believe what the amorphous blob that is ‘mainstream culture’ does very well is it archives itself. Something is deemed significant and is then reproduced as articles, documentaries, the full array of interviews and discussions and retrospectives and anniversary releases and repackaging and new formats and so on: that’s an archive.

Underground culture tends to become a footnote in mainstream stories—while its own specific and unique stories fade away

— Nick Soulsby

Underground and radical culture relies on far smaller resources, not just in terms of money and the means of production, but even just related to people’s time. Without the diversity of channels, motivated individuals, and the ability to duplicate itself, underground culture tends to become a footnote in mainstream stories—while its own specific and unique stories fade away. I feel it’s vital for those voices and experiences forged outside of formal, official, professional channels to be recorded or they die. By die, I mean quite literally—people die, and often far younger and more unexpectedly than anyone might wish.

The participants in a scene are usually too busy making things happen to spend time documenting it, but there’s ineffable benefit to someone in the circle choosing to do so. Similarly, at some point, it’s great when people get their tale down on paper—I’m working on a book now where, during the writing of it, more than half-a-dozen interviewees or potential interviewees have dropped dead just in the last year. Life!

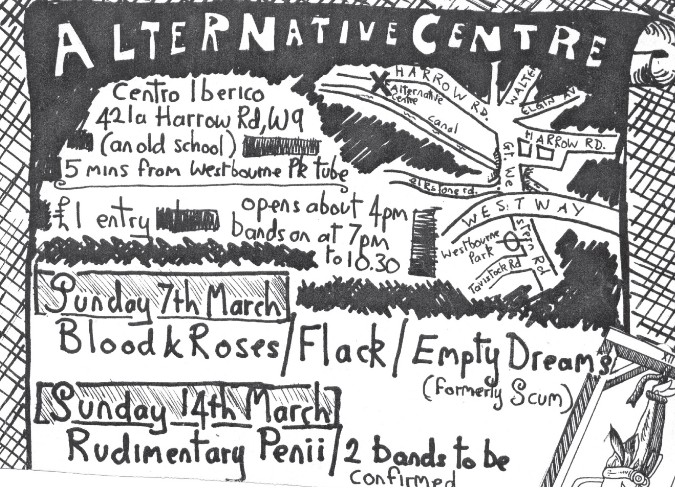

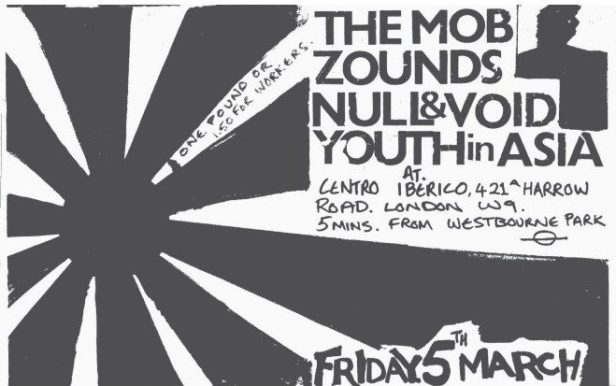

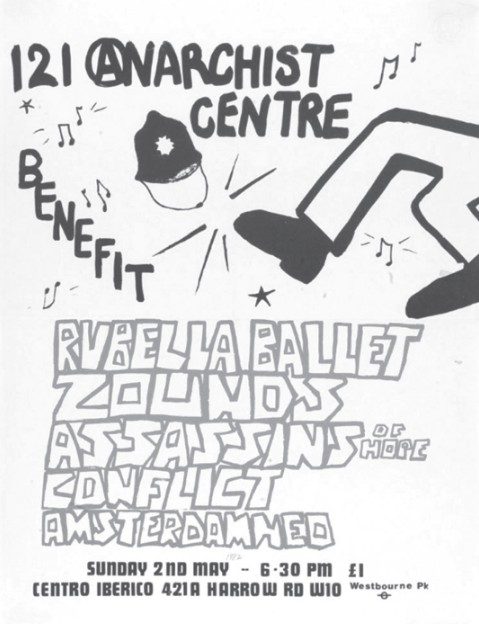

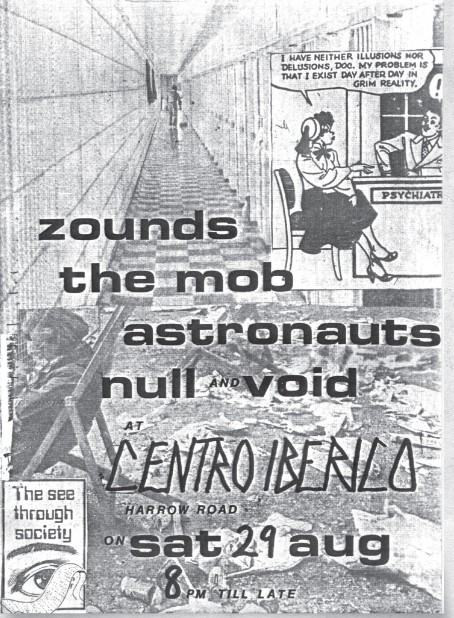

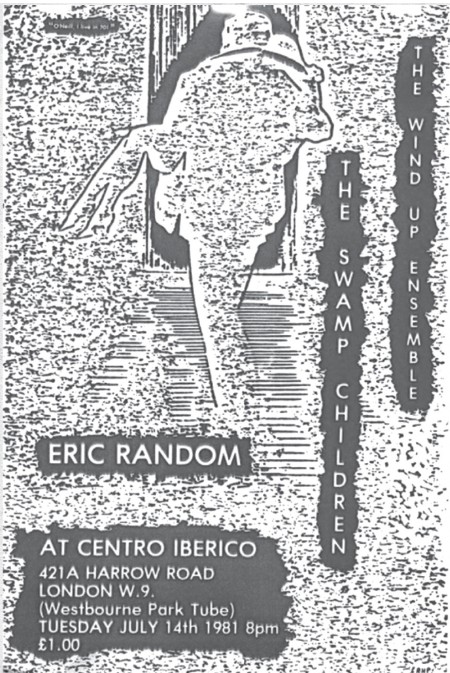

The underground, generally speaking, and music or youth culture overall, is often resistant to paperwork—to preserving the prosaic documentation indicating the day-to-day hard facts of organising a space, staging events, and so forth. Finding gig listings for Centro Iberico in the back of Sounds was a thrill, the newspaper article recording when the school closed, a list of gigs played by The 101ers—Joe Strummer’s band prior his punk conversion and the founding of The Clash—including a likely date for the first gig at 421a Harrow Road, the original planning documents for the building, and the posthumous record of the demolition. All very exciting!

So much of the time, the traces that remain are experiential, these shreds of memory that morph and warp in ways that make it hard to verify what really took place. As examples, two of the most detailed tales found online—that there was an attempt at the Conflict gig in August 1982 to lead the crowd outside to stage a riot, and that there was a final gig at the venue in early 1983 while the residents were packing to move out—there’s no indication that either tale is anything more than wishful thinking. In the latter case, none of the bands supposedly involved have any recollection whatsoever. The former, meanwhile, just makes no logical sense.

Who did you speak with, and what archival material were you able to access?

A solemn bow of respect for the work of The Sparrow’s Nest Library and Archive. It’s an extraordinary thing to have a full library and archive of anarchist and radical sources gathered together, with a commitment to digitising and making such sources available. The team involved there—I’m genuinely humbled by the scale of what they’re trying to do in capturing, preserving and sharing as much as they can of Britain’s anarchist history, on shoestring budgets and vast passion. What a lovely bunch of people too! If anyone has original materials they wish to see become part of that collective story—please, I can only encourage them to get in touch and give what they can.

The City of Westminster Archives team were very helpful in locating files related to the building, the original school, and the building work that took place to redevelop the site in 1983-1985.

The Jackson’s Lane Art Centre were able to help with information about its early days when Centro Iberico had a temporary home there, likewise, the Church of the Holy Trinity, Kingsway, permitted me to include an era-specific image of their building, also a temporary Centro Iberico home.

The information online was severely scattered: the Wikipedia entry was eight lines mostly listing band names—I’m quite chuffed to see that, coincidentally or not, there’s been a major upgrade to the Centro Iberico Wikipedia page in 2025. Sources were able to speak to one moment or another, usually eyewitness testimony, stray photos, the odd gig recording. Part of my desire was to try to draw these disparate and fragmented perspectives into a single, coherent pattern.

Most crucially, there’s a community of amazing people who survived that era and know that this is the moment to preserve memories of what occurred. I spoke to members of numerous bands who played at the venue, I spoke to two Spanish individuals who had lived at the school, one former member of the Centro Iberico in its pre-school era… A healthy constellation of voices.

Can you say a little about the up illustrations you’ve been able to source for the book?

Financial limitations, given this is obviously quite a niche work, meant we could only reproduce illustrations in black-and-white—which is perfect for the majority of the material, and gives a very united and coherent feel to the volume.

However, one downer—in some of the photos of the Alternative Centre space, it’s harder to distinguish the remarkable array of murals that the people running the gigs painted across the walls of the former gymnasium. It’s worth looking at the Kill Your Pet Puppy web archive to get a feel for things.

Otherwise, one factor that influenced my thinking was that I doubt there’ll ever be another dedicated volume focused on Centro Iberico. So I wanted to capture as much of the visual and documentary record as possible within the book’s pages to ensure that it’s all there in one place, for anyone interested, or with their own ideas that might play off of these sources.

Numerous people were generous with their personal photographs, and that lends the human feel to the visual record. Likewise, I was obsessed with tracking down gig listings, flyers, people with tape recordings—anything that might pin down the dates and timeline of Centro Iberico’s existence as a creative arts space from 1975 onward. Understandably, there’s a lot of ‘shadow.’ I was lucky enough to wind-up in touch with someone who lived at the school from 1979 onward and who staged a lot of the musical entertainment: a guitarist called Eduardo Niebla who performs to this day over in Spain. Eduardo kindly pulled items from his personal archive and sent me photos of them, so at least some small part of the Spanish residents’ events remains. But there are dozens of such moments that we can surmise—but not prove—took place.

I doubt there’ll ever be another dedicated volume focused on Centro Iberico. So I wanted to capture as much of the visual and documentary record as possible

— Nick Soulsby

Did what you discovered about the Centro Iberico match up with your expectations as you began working on the book?

I honestly and truly had no expectations. It was a total mystery to me, so all I had were questions. I was born in 1980, so my experience of London really starts to form from 1999 and really expands after I move there in 2004. Looking at the commercialised bustle of modern London, Centro Iberico felt like a modern myth to me: the idea that, once upon a time, there was an entire Victorian school, four floors and dozens of rooms, overlooking a major London street, and someone could walk in and occupy it as creative space and home for the best part of a decade… Revisiting London in the 1970s, on into the early 1980s, is like taking a trip to a foreign country.

The people who were a part of the Alternative Centre—or even people who were present before that—they often knew nothing about the history or roots of Centro Iberico. William Orbit, for example, lived in the old caretaker’s cottage on the playground for five years, and he and his compatriots were always puzzled why there was so much scrap metal, and so many old metalwork tools, in sheds at the back of the playground, because they didn’t know that, for twenty years, the school had been used in the evenings as a college for Adult Education—it was fun being able to fill in gaps in people’s sense of the space.

Likewise, moments of discovery mean a lot to me: I likely shouldn’t get so excited by details like these, but the day I found a newspaper article that allowed me to pin down the exact week the school was squatted—initially to prevent acts of vandalism that had taken place when the building was empty—I think I likely danced. Same with the gig listing in the back of Sounds that recorded the date in September 1982 when Richard Rupenus and his brother, Philip, accompanied Nigel Jacklin to the old school to put on a show. That answered that very first question for me: Richard and Philip did perform at Centro Iberico two years before TNB got going, as part of Jacklin’s Alien Brains project, with the gig listing including the name of their sound collage project Bladder Flask, just to beef up the entry and maybe encourage a smattering of attendees.

How did the existing anarchist militants respond to the arrival of the political punks and the transgressive punks at the Centro Iberico?

I have empathy with perspectives from all sides. The idea that ‘many different things can be true at once’ and that ‘you have to accept that contradictions will exist’ won’t make anyone’s head explode. The political anarchists who cut their teeth in the post-war era were generally older than the punk generation. It’s also true that the anarcho-punks of 1979-1982 were very different to the original punks of 1975-1978—when it comes to young people, even a gap of a year can seem a lifetime. Undoubtedly, some people crossed over or straddled these spaces, there are always exceptions.

I can absolutely understand why the established anarchists were so hostile to this new generation who, in their eyes, lacked any sense of the basic principles of anarchism as a creed, philosophy and historical phenomenon—they were right!

I can also understand why the young punks rebelling against school, parents, and amorphous authority didn’t want to be given more homework, and felt that they were forging a new form of anarchism summed up as ‘strive to survive while doing the least harm possible’—which was more human and less doctrinaire.

The history of the British left, tragically, has always been one of purity testing leading to endless schisms and the voiding of power.

What heartens me is seeing things like Rockaway Park near Bristol. Mark Wilson of The Mob has really achieved something special, a world of support to people in need, space for individuals to pursue their visions, engagement with the local community and encouraging people with different perspectives… Seeing people holding true to core principles, not giving in or giving up, and greeting the world with a smile, really uplifts me.

There was always these two different strands—we just have better documentation of the punk component

— Nick Soulsby

How far should we see the Centro Iberico as a descendant of the earlier London Autonomy Centre?

Between 1971 and 1982—that is, for more than 90% of its lifespan—Centro Iberico has nothing whatsoever to do with the Autonomy Centre. Centro Iberico exists initially as a peripatetic concept wedded entirely to the figure of Miguel J.M. Garcia. It drifts through three different locations across that time.

Part of my desire in writing the book was to really pin down, as close as possible, the basic timeline of those movements and the expansion or contraction required in moving from a church —where it can only meet for a few hours on Sundays; to a dedicated basement—where weekday evenings and entire weekends become a possibility, and back into the restricted hours available at a multipurpose community arts space.

In that time, it’s dedicated to bringing together the Spanish diaspora in London which had heavy familial and personal ties to the defeated Republican forces in the Spanish Civil War and to the anarchist brigades, to building links with local London-based anarchists, and acting as a hub in a wider European network of political allies.

In 1978, Centro Iberico moves to the abandoned school at Harrow Road and Garcia eventually retires to Barcelona. The school had been squatted since 1975 and a small core of Spanish nationals have wound up in residence—which is what draws Garcia there, and why it’s in no way incongruous that the location becomes known as ‘Centro Iberico’ from then on, as a mark of respect to Garcia and as a declaration of identity.

There have already been gigs there as early as 1975, and the years 1978-1981 are an underappreciated hotbed of activity: they’re hosting gigs, art shows, allowing people to film amateur films on the premises, and staging Spanish cultural events including music, poetry and film screenings. Then there are also political meetings and events, even pamphlets and flyers being produced around particular causes. While the anarchist press only grudgingly acknowledges its existence—because the squatters at the Centro Iberico don’t formally identify with the anarchist movement in the way Garcia did—it’s already a functioning establishment.

For six months running from March to August 1982, the ‘Alternative Centre’ at Centro Iberico on Sundays is indeed the successor to one part of the Wapping Autonomy Centre: in the guise of the gigs. Even then, the existing residents are running their own schedule of events at the venue, independent of that. So there was always these two different strands—we just have better documentation of the punk component. The Whitehouse gigs, for example, are nothing to do with the Alternative Centre. They’re negotiated by Jordi Valls, a Catalan artist and manager to Whitehouse, directly with the still-present Spanish residents.

As far as the political anarchists’ vision of Wapping, there’s not really a successor—although some strands of the activities could perhaps be seen as surviving at the 121 Centre down on Railton Road in Brixton.

Some suggest that the culture of Centro Iberico was in practice ‘less political’ than the London Autonomy Centre. Is that a fair assessment?

Absolutely. The Autonomy Centre is a pretty abject failure as a political project—a case study in poor financial management and poor organisation, wildly inflated illusions as to its viability, and ideological rigidity, manifesting as snobbery and aggression, toward its primary audience.

There are photos, one in the book and another I wish I’d seen in time, of graffiti on the wall at Wapping insulting and sneering at the punks who were pretty well the only income the Centre ever had. It was the punks who had pulled together the majority of funds to support the Persons Unknown defendants; it was Crass and Poison Girls and their fans who had provided most of the funds to bring the Autonomy Centre into existence; it was the gigs that provided the centre its one chance of surviving… And the political anarchists acted like they were running a school, with the punks as unruly and unworthy children.

The Alternative Centre at Centro Iberico saw the punks themselves running the show. It’s more coherent and effective on that basis, but distinctly more cultural than political. Political activity is distinct from singing songs. One’s personal life can manifest political principles, but it’s still different from the active real-world fight to change other people’s living conditions and the entire social and economic system. The two are not synonymous.

Centro Iberico reaches its peak in 1979. The building, though dilapidated, is still sufficiently intact, and there’s a core of people in residence able to maintain and organise its use

— Nick Soulsby

From the way you describe it, there seem to have been few gate-keepers who would try to obstruct anyone keen to perform at the venue — how far was it an ‘open stage’ policy in practice?

Oh, there’s always a gate-keeper of some sort! The Alternative Centre is very much a circle of friends asking friends—Scum Collective making the decisions one weekend, Kill Your Pet Puppy the next—with the resulting bookings producing a fairly steady lineup most weeks, with only a few genuine curveballs.

The Spanish squatters, likewise, are mostly making their own entertainment, or bringing in personal friends. But it is true that people would ask them if they could use the space—and that results in things like anarchist conferences being held there in 1979, and Whitehouse and then Alien Brains performing in 1982. It may have been informal, but there’s still visible authority at play: the squatters ‘own’ the space and seem to have said ‘yes’ to anyone who asked to use Centro Iberico. They grant authority to the Alternative Centre to use the first floor hall, initially; then the ground floor after that. It’s also the squatters who would, at some point, have allowed Garcia to take over a classroom for Centro Iberico meetings.

It is true that the organisers themselves might put together a scratch band just for fun or to fill time, but that wasn’t common practice at all. There is one case where a poet, a friend of a performing band, went on to do a few readings. But I didn’t see any mention of someone just rocking up with an instrument and asking to play. There was no ‘open mic’ night at Centro Iberico.

When did the Centro Iberico reach its peak, in your view? When were its finest hours?

Centro Iberico reaches its peak in 1979. The building, though dilapidated, is still sufficiently intact, and there’s a core of people in residence able to maintain and organise its use. The adoption of the name ‘Centro Iberico’ and Garcia’s departure for Spain, leaves a legacy of active political activity taking place that year. Most crucially—musically speaking—Throbbing Gristle’s decision to perform there in January 1979 grants the venue underground cachet and cool.

By 1982, the space is a life-raft for the shipwrecked punks who had enjoyed playing Wapping. But it’s very much an Indian Summer for the venue: it’s no longer truly liveable; the space is silent most of the week. There’s an ever-increasing feeling of inevitability to its end.

What would you say connects the experience of the Centro Iberico with later developments in the anarchist and punk scenes in the capital which developed in the 1980s?

In some ways, the fate of Centro Iberico is a harbinger of what would come. The swell of ‘alternative lifestyles’ across the 1970s, was meeting an ever-increasing pushback from an establishment that considered non-participation in the economic mechanisms of capitalist society an anathema. The turn in London’s fortunes would gather pace across the rest of the decade, driving squatting even further to the margins by strangling the supply of potentially useful properties. Those who wished to organise and survive formalised their activities into housing cooperatives—which did a lot of good—or other officially established setups.

There was also the basic challenge of human nature. At Wapping and at Harrow Road, there was always the gap between the people with the industriousness and spark to make something happen—motivated by the willingness to back the life they wanted to be a part of with actual action—versus those who just wanted to consume the results without putting anything back in.

I am incredibly energised and humbled when I see individuals pour work into bringing a vision to life, for no reward other than the experience itself. Speaking to people like the Kill Your Pet Puppy collective, Tony Drayton and Mickey Penguin specifically, it just awes me. The work of keeping the Alternative Centre going, it was too much in the end. It was easier to move over to venues like The Batcave when it came to musical entertainment, friends’ homes when it came to community, and actual political organisations like Class War for activism.

Again, maybe that’s a general learning from both the Autonomy Centre and Centro Iberico—that an institution divided against itself cannot stand for long. In each case, trying to straddle philosophical divisions, while also trying to be multiple things simultaneously, there’s only so much energy to go round—and it makes it hard to do any one thing to its fullest extent.

More positively though, I’m seeing that, to this day, motivated young people always find a way. Here in Bristol, I attended the Monochrome: Festival of Ugly Music in 2025 and I’m booked in again for 2026. At 45 years old, I was likely the oldest person in the room—and it was an absolute tonic for my soul. The bands and artists stuck around to support one another from the audience, there was this visible collective energy and acceptance for one another with everyone making these remarkably ‘out there’ sounds… It was amazing. Sure, the majority of people might be too lazy or too defeated to think of culture as something they create rather than something they consume. But there’s always that core of individuals who refuse to surrender their right to make it something all their own. If I may make a major bow of respect to the Margin Forever Collective, to Obnoxious Concoction, HORSEBASTARD, Victim Unit and Gorgon Vomit… They warmed my heart.

Nick Soulsby. 2026. Born of Struggle, Living in Hope: The Anarcho-Punk Lives of the Centro Iberico, 1971-1983. Oakland, CA: PM Press. 9798887441221 (paperback).

Order from PM Press (USA) or PM Press (UK)

Miss them days, the gigs the people