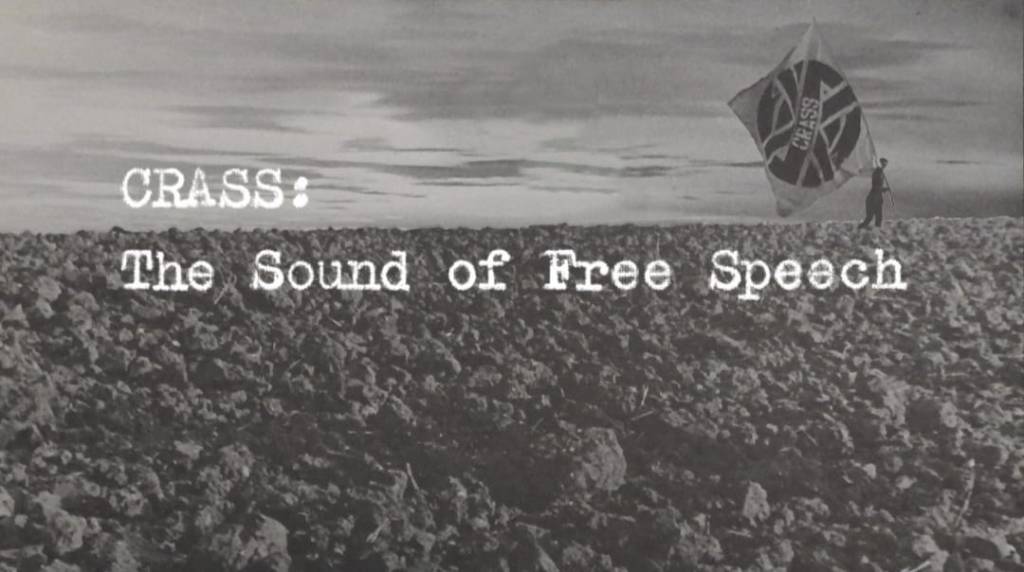

Brandon Spivey, director of new documentary Crass: The Sound of Free Speech talks to The Hippies Now Wear Black about DIY filmmaking, the importance of assertive atheism, the significance of Reality Asylum, the complexities of ‘Crass and class’, and audience reaction to his intense 90-minute exploration of the band’s first – unparalleled and unmatched – seven inch single.

What was your first connection with Crass? What was the first thing you heard?

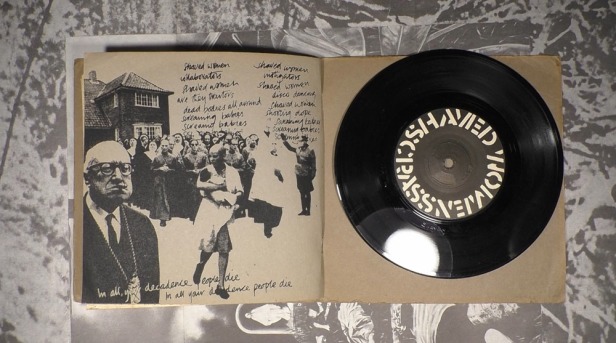

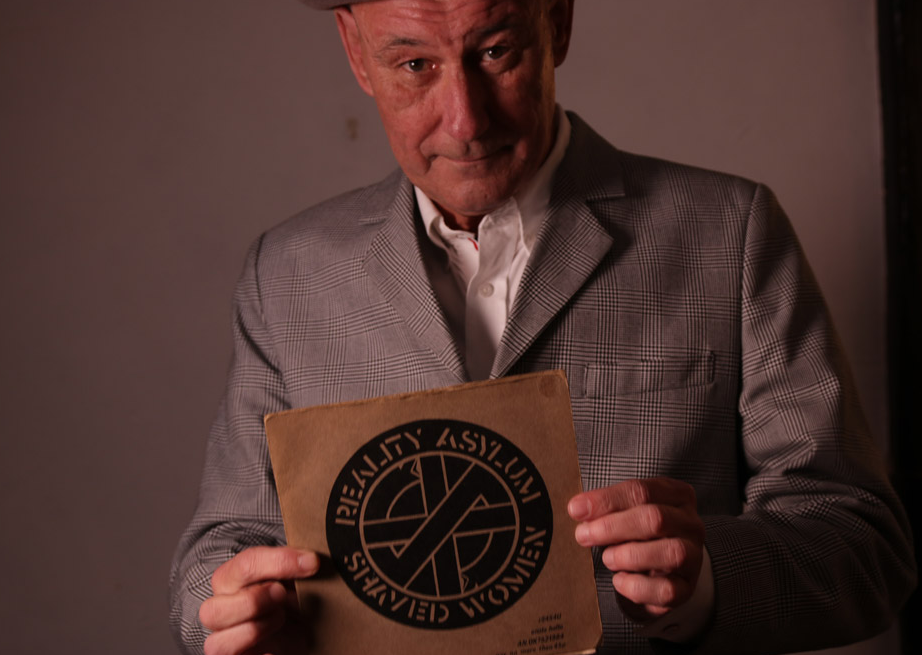

I got into Crass when they started, really. From Feeding of the Five Thousand but the first thing I really connected with was Reality Asylum. It blew my mind. I first heard it as a young kid, I think I would have been 12. Me and my mates all listened to that seven inch single, and my mates liked Shaved Women, and I preferred Reality Asylum.

It was an unforgettable moment, hearing that song. When Eve Libertine spoke, hearing her say those opening lines, it was so powerful. It was a big deal when I heard it, you know? A seriously big deal. It was genuinely life-changing.

What sense did you make of the politics of Reality Asylum?

I didn’t have the language! I wasn’t articulate enough. I could relate to the stance more than I could the politics. Later on, I could relate to the anarchism, the anti-authoritarianism and the rejection of religion. But, to begin with, it was the stance that knocked me for six. That complete contempt for authority. I discuss this moment in the film.

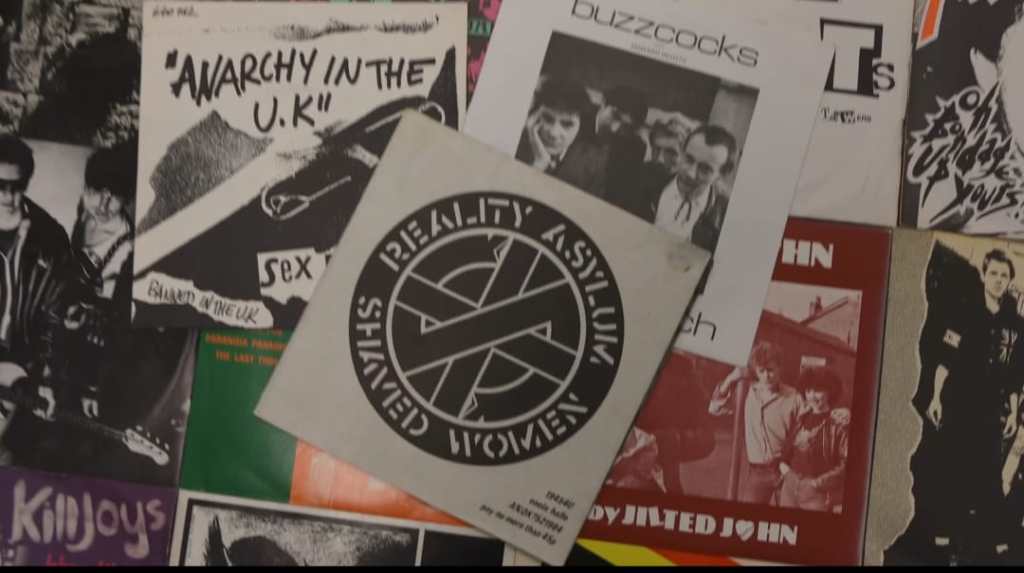

And, in terms of impact, I don’t think anything’s ever matched it. From around the same period there were releases by bands like Joy Division, Throbbing Gristle, Cabaret Voltaire and others. They were all ‘ground breaking’ sonically. Clearly they were significant artists. But for me Reality Asylum was a record that cut through all that stuff, to make a political statement. It was so significant.

Did it encourage you to explore politics further?

Yeah, without a doubt. I mean, for me, to this day, it’s still a very important reference point in my own radical politics. It was hearing Reality Asylum that led us as teens to start going into radical bookshops, and picking up things like Spectacular Times and Black Flag and Freedom, and also Irish Republican stuff like An Phoblacht. I managed to get my hands on the International Anthems that Gee Vaucher produced. And I started, almost subconsciously to begin with, to track down the work of other artists who were putting out a strong anti-war, anti-religious message. I got into the work of George Grosz, the Berlin Dadaists and Otto Dix.

One of the reasons I made the film is because of being into Dadaism. Growing up, I got to know a guy called Mark Scurrah. He played briefly with the Blue Orchids in Manchester, and he turned me on to George Grosz. So as a 17-year-old, living in a shitty block of flats in Macclesfield, I got into Grosz and I was totally blown away by the Dadaist artists of Berlin from the Weimar period.

They have continued a tradition of intensely critical, anti-authoritarian art that you can trace back to the 1920s.

Brandon Spivey

Years later, I now actually own a signed George Grosz litho, and I’ve got some first editions of his books, and I’ve travelled to loads of Grosz exhibitions. (this is another form of record collecting for me, tracking down those rare inspirational ‘Records’) I’ve come to realise that Gee Vaucher and Crass are, in the same sense that Grosz was, degenerate artists. They have continued a tradition of intensely critical, anti-authoritarian art that you can trace back to the 1920s. I see the aesthetics of Crass – the sound, the sonics, the imagery, the presentation – as part of the development of degenerate art, of Dadaist art. I see it as part of the continuation of an extreme, but wholly justified, artistic reaction to a brutal, alienated society.

How did work on what became The Sound of Free Speech start?

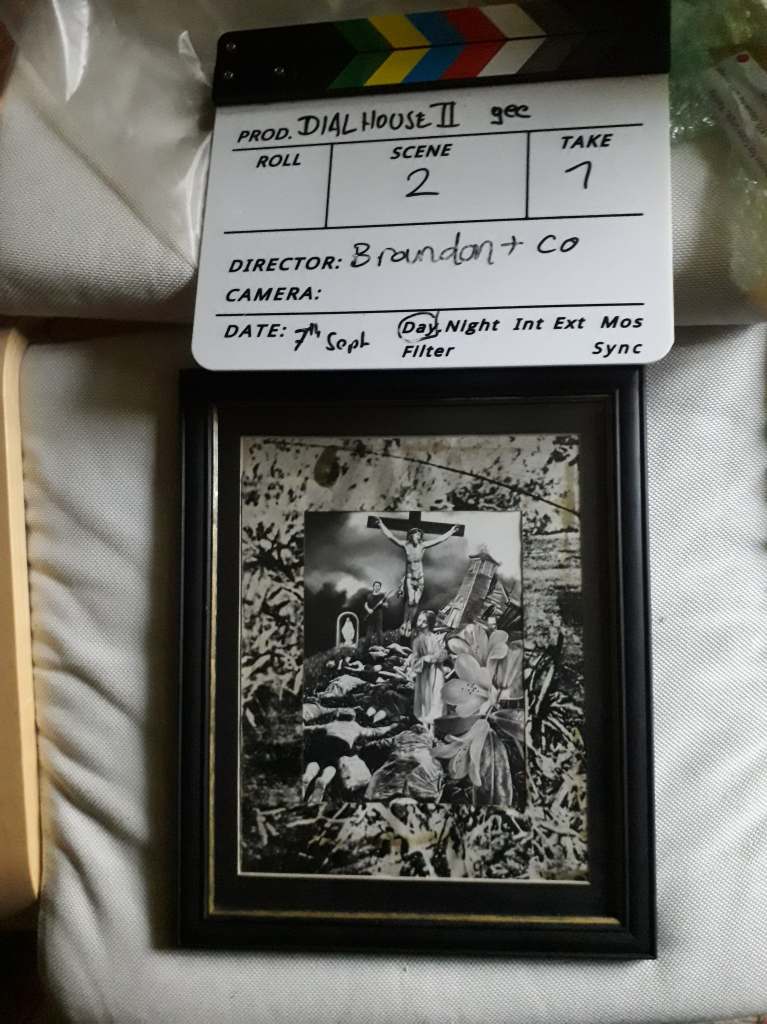

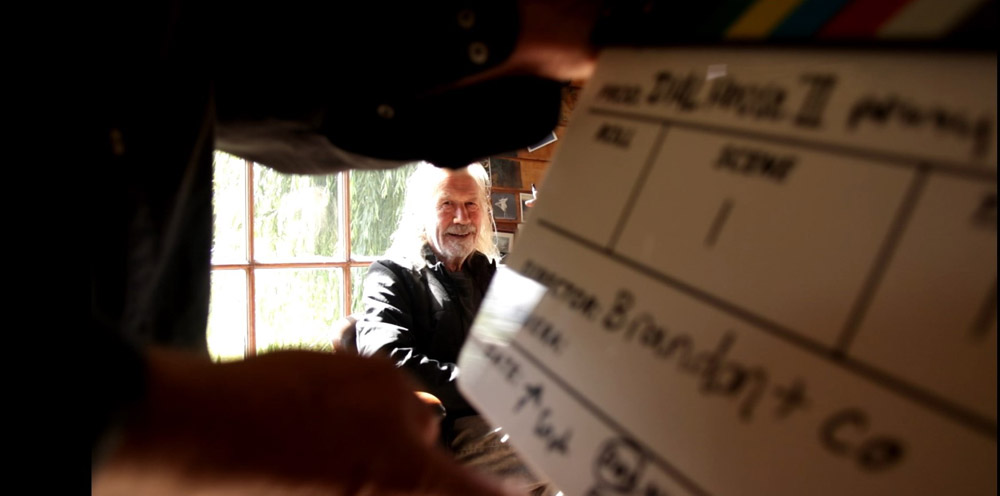

Initially, we were going to do an audio interview with Penny Rimbaud, about Reality Asylum. And as time went on, I got to know quite a lot of filmmakers. So I asked Penny if he would consider it being filmed. He said he would prefer it. So we decided we’d put together a film on the making of Reality Asylum and its impact on people. So that’s what we’ve done. So we went down to Dial House and did four days of filming. Penny was very receptive to the idea, and he didn’t hold back on the detail. We spent a lot of time with him, and recorded hours of footage. He talked about a lot of things, including the story of Wally Hope, and we went off in all kinds of different directions. But we all knew that we had a job to do, a thing to focus on. And that was to tell the story of one seven-inch single.

Gee Vaucher was fantastic too. She allowed us in the studio and, over a couple of sessions, we covered a substantial amount of things. We found out a lot about her life as well as about her artistry and her artwork. It was snowing while we were there, and we took some great footage of that, and of sunrises and sunsets over Dial House. That’s how we started.

I’m not particularly connected with the modern punk scene, and I couldn’t get hold of Steve to begin with. When I did, Steve and Jona were incredible and supportive. Andy T was wonderful, so were Pete Stennett, Mick Duffield and so many other contributors. Annie Anxiety Bandez – Little Annie – came over to Europe from Miami. We were very, very lucky. We were able to film Annie in Berlin, on the street outside the Olympic Stadium built to glorify Nazism at the 1936 Games. She also returned to Dial House for her interviews with us. She had not been back there in a long time, and I can’t thank Annie enough for that.

Has the film been a solo or a collaborative project?

I am credited as director and producer, but I’m pleased to have been able to collaborate with such a good gang of people. I work closely with Laszlo Umbreit, a Brussels native. Umbreit and I have done a number of in-depth audio interviews to do with music and culture together. He was involved with this film from the beginning, and with Laszlo in control of sound recording I knew it was a credible project.

Also involved were Sansculotte, Sandra Dollo and Uli Berthold in Berlin, who are friends of mine from the techno scene. They are a great camera crew, impressive film editors and also handle digital effects. When they also agreed to take on the project, I knew that we had an impressive team more than capable of making a convincing film. Mike Whatmore has also played an important part in the production of this film.

Everyone who worked on the film in their own right fetched a lot to the table. I was proud to have the skills of Mick Steff and Billy Foster on the film. They are lads from my home town who both are part of my history and friends to this day.

How have you been able to fund it?

I am a builder and worked hard to earn the money to make the film. Well, all I though was ‘fuck funding’, because all it means is compromising and kissing arses. I do believe in the essence of DIY – one hundred percent, you know? And I stand by that decision, not to apply for funding. It would have held us back, rather than move us forward.

It has cost a lot of money. It’s left me broke but, you know, if you’re going to make a film like this, it is worth investing that level of energy and money and time. Future Class and Culture films will explore all available funding avenues – so anyone wanting to financially support our filmmaking work should get in touch.

Was it difficult to keep the film’s focus on a single record?

What I needed to do was to explain the context, the 1970s – but without losing the focus. I had to consider people seeing the film who didn’t know anything about the band. I grew up in Oldham, and The National Front were on the streets at the end of the seventies. The film discusses censorship in art at the time, and the court case over the Kirkup poem in Gay Times, but I had to keep things focused.

It was Penny Rimbaud who wrote Reality Asylum. Steve Ignorant founded Crass with Penny. There’d have been no Crass without Steve, and there’d have been no platform for Penny without Crass. I had to tell the story of how the band began, but I had to keep the focus. Every now and then I would include something new, and then think ‘well, it’s interesting, but it’s throwing the film off course’, and take it out again.

As the film developed, did the project develop in the way that you hoped?

Yeah, it did. It certainly did. I had a vision of what I wanted. I wanted to present everybody honestly, and I wanted it to look beautiful. Even though some of the subject matter is very macabre – and Reality Asylum itself is very brutal – I wanted to balance that with beautiful imagery. So ‘cinematically’ – a word that’s still strange to hear me say – I’m very happy with it.

It is not a ‘rockumentary’. Enough people ‘idolise’ Crass and seem to miss the message. The film is about what they produced and did, and not about what went on amongst them – other than their creative output.

There’s also a lot of authentic ephemeral detail in the film – something that’s in the sound design too. The sound of the needle going down on the record, the crackles and pops as the vinyl plays, the sight of the stencil duplicators people would print fanzines on, images of the sleeves of punk singles. I wanted to capture the atmosphere of what that period of subcultural life felt like, around 1979.

We recorded both Reality Asylum and Shaved Women for the film’s soundtrack from the original Crass Records vinyl. A friend from London called Leigh Dickson, who I know through the techno scene, made those initial recordings. And when I got the edits back, he’d cleaned up the digital copy, removing all the pops and scratches. I said to him, ‘fuck me, man, those are what I wanted.’ So they got put back on. I owe him a pint!

The fact that it’s taken a lot of time to complete the film has allowed different things to come forward and get included. Now that Dave King, who created what became the ‘Crass logo’, has sadly passed away, his estate has been so helpful. They provided us with images of the original artwork for the cover of ‘Reality Asylum’, in its original booklet form – which even Penny did not have access to. What you see in the film is David King’s copy. You see a hand placed on it, and that’s Marcy’s, who represents the estate.

The fact that it’s taken a lot of time to complete the film has allowed different things to come forward and get included.

Brandon Spivey

It’s fair to say that some of the people I worked with didn’t fully understand the vision to begin with. The archival footage of concentration camps was difficult for some. I worked with some German colleagues, and that sort of material is really sensitive stuff for them. That took a long process of communication to fully resolve. I did a lot of research, looking through material from that period. I got permission from the Holocaust Museum in America to use footage and that included scenes of Nazi collaborators having their heads shaved and of concentration camps. That research was all about trying to find stuff that was poignant, you know?

I do think that everything in the finished film is poignant. I don’t believe that there’s a single piece that’s – what’s the word – gratuitous. It’s all there to tell the story. So I’m very happy with it. A lot of consideration has gone into The Sound of Free Speech. Right at the front of the film Penny Rimbaud says ‘I saw society like a concentration camp’. And when people understood the context, and that it wasn’t some appalling fetishism of Nazi imagery, they were able to say ‘oh, we get you now.’

We’d come almost to the end of the final edit film when I came across Tom Rhattigan‘s Boy Number 26. And I just couldn’t ignore Tom and what he had to say. We had potentially about five minutes running time to play with, and after we spoke with Tom we had to make the decision. ‘OK. What an extraordinary, personal perspective on the horrors of the abuse of children at the hands of the clergy who were supposed to care for them – do we put it into The Sound of Free Speech?’ We did, and it helped to connect everything.

After I showed Penny the final cut, he said that Tom’s inclusion was a really big deal, and took the theme of the record further than he could himself. He’s very complimentary about it.

What’s your take on Crass and questions of class?

I do get people saying to me ‘Crass? They’re all middle class.’ I am a working class activist, and I am very class conscious, and there have been some critical voices asking ‘why’s he making a film about fucking Crass?’ Well, Penny Rimbaud might come from a middle class background. He wears his heart on his sleeve. And I admire Penny, because he’s an honest fella, and he doesn’t give a fuck. He’s got the bottle to live how he wants to live, and just says ‘this is me’.

Gee Vaucher is working class, brought up in Dagenham. Gee went to a school where there were no exams, because you were going to go straight into the factory when you left. Steve Ignorant is working class. Everybody warms to Steve because he’s a fucking great fella, who’s full of common sense and decency and street knowledge. So, hang on a minute, how come ‘Crass are middle class’ then? How the fuck does that even work when one member might be? And for a lot of working class kids, Crass opened our minds up, at a time when the left was a fucking joke. Billy Bragg? Red Wedge? All that fucking rubbish, and the rubbish that came before that. It didn’t touch any of us. It didn’t go anywhere near our lives.

So, as a working class activist, I’ve got no problems doing a film about Crass. Penny Rimbaud says, at the end of the film, ‘it’s all about class war.’ He’s right. It is all about class war.

Any idea that cannot be ridiculed, scrutinised and laughed at is authoritarian in nature

Brandon Spivey

I am coming at this from a working class perspective. I have a memory of being in the Cubs, as a kid, at this place called the Hollywood Working Men’s Bible Mission. And I ‘blasphemed’ and this Akela came down really heavily on me. Even then I thought, why can’t I criticise religion? There was no context in which I was allowed to say religion’s bullshit. That Crass record did, and this film does. And it’s really liberating to hear someone say it so powerfully.

The uncompromising expression of atheism is vital, especially because there’s still so much politeness and tiptoeing around religion and other doctrines and dogmas. Blasphemy is a vital human expression. People are getting killed across the globe for expressing contempt for religion and authoritarian doctrines. Any idea that cannot be ridiculed, scrutinised and laughed at is authoritarian in nature. I do go along with the idea that ‘without free speech, we don’t exist’. The film is a celebration of free speech. The importance of defending the idea of free expression is something reflected in the words of Pete Stennett of Small Wonder in the film, and the opening track from the Feeding of the Five Thousand.

Has it been easy to find an audience for the film?

I made the film without much consideration about what would happen after I had made it. I didn’t make it for the ‘marketplace’, and that meant I didn’t compromise over the contents. I realised that I had to make a film that was instinctively authentic for me, as somebody who was into Crass as a kid. I didn’t have much knowledge about the film industry, and very little experience of what was involved in getting a screening at a film festival.

The film was selected for the programme of the Berlin Soundwatch festival. Soundwatch is run from an old squat, a former butchers’ shop and one of the oldest buildings in the city, that’s been turned into a cinema. It’s the most beautiful place to show the film. And it came joint first in the festival, an audience award voted for by those who were there, alongside Mutiny in Heaven, the Birthday Party film. I was very proud of that. I was proud of that because Berlin was Nick Cave’s old stomping ground. And I was also very proud to take some of the shine off Mutiny because the bastard played in Israel.

That award validated the film, and then allowed us to start displaying the laurel wreath symbol when listing the film – something I didn’t know anything about before then. And that was the beginning of the film festival side of things.

It recently had two screenings in Italy, and it’s just been shown in Poland. The Film was selected for the SeeYouSound Festival in Turin. It is a very prestigious film festival and there’s strong competition amongst international music documentaries. It was only one of six films to be selected. We’ve had screening requests from France, and from Spain too – so we got extra subtitles done. I’m very, very pleased with the way that it’s taken off. And I didn’t fully appreciate this, but there are Crass fans everywhere. Crass fans in places you don’t expect them, and they’re very privately saying to me, ‘will you come to our film festival?’ I will be going to as many of the screenings for Q&A sessions as I can.

Will the film also find a home on DVD or on online streaming services?

There will eventually be a DVD release, complete with extras. That’s the goal, but that can’t even be considered right now. That will include more amazing interview testimony and lots of in-depth stuff. But that will all be later. Right now, we’ve got the film screening at festivals and in cinemas. The film has been picked up by Doc’n Roll, who’ve got an impressive track record of promoting films. I’ve seen the work they’ve done with Aaron Trinder and his film The Free Party. Doc’n Roll want it to reach bigger audiences, and with their help word about The Sound of Free Speech is getting out there, and people are really keen to see it.

The film is getting queued up for mainstream streaming services, including Amazon and Apple. I can live with the contradiction of that, as it means that the film will reach a seriously wide audience. So, yes, it will be streamable on major online platforms in the not too distant future.

What sort of reaction has there been to the film at those early screenings?

I’ve met people who were very inspired by the work of Crass and of DIY punk culture, but maybe took those kinds of ideas in a different direction. Crass were very influential. But it’s important to make the point that I’m not a sycophant towards anything or anybody. I grew out of the punk thing in about 1984 during the miners strike.

I realised the punk thing didn’t really do anything for me, and I moved in the direction of politics and campaigning. I’ve been involved in many heavy-duty and effective campaigns, like the Hillsborough Justice Campaign, The Armley Asbestos campaign, Troops Out, and anti-fascism. I wrote No Comment: The Defendant’s Guide to Arrest. I’m an anarchist, and I’m involved in stuff, but – no disrespect to anyone who disagrees – hardcore punk means fuck all to me now.

Because of the contents of the film, it is striking a chord with a lot of people. I showed the film in Manchester the other month, and there was a guy there, a Crass fan going back many years, and he said, it put the hairs up on the back of his neck. I know that some of the people watching the film have had a pretty tough life, and that Crass has meant a lot to them. And when I’m hearing things like that from people, it is a big deal to me.

A lot of people seeing the film are really moved by it. And that has surprised me. People want to discuss it afterwards. After the Q&As, people are coming up to me and shaking my hand and thanking me. I’m happy, very happy, with the reaction. When I was making it, I really didn’t think about the reaction the film might receive. It’s all made me realise that, one way or another, I made a powerful film that does not compromise.

CLASS AND CULTURE FILMS can be reached at classandculturefilms@gmail.com or by calling 07913 378937 (09:00-17:00).

“Class and Culture Films are looking to produce more relevant and hard hitting films that are accessible to all. We are looking to raise money – via donations, subscriptions and funding – for our next projects. If you have an interest in such productions, please get in touch.”