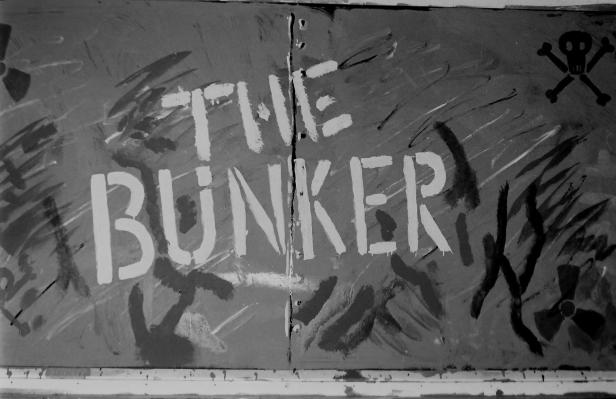

LATER THIS MONTH, A SERIES of events will mark the thirty-fifth anniversary of the opening of The Bunker, the celebrated Sunderland DIY music venue and organising centre that, at each of three locations it occupied in the early 1980s, played host to many memorable anarchist punk gigs and which sought to put into practice the principles of an independent, and genuinely rebellious, punk spirit. Two members of “The Bunker Group 35“, Alan Christie and Andy Hardcore, spoke with The Hippies Now Wear Black about the life and eventful times of one of the north-east’s most distinctive punk venues.

What were the catalysts that led to the establishment of the original Bunker?

Sunderland punk bands in the late 1970s and early 1980s had no base to practice, and had to pay stupid money to rehearse at so called “professional” practice rooms. Youth unemployment was running at 40% in the early 1980s. Everyone was skint. So it was case of rehearsing at friends’ houses, community centres and church halls. This meant hauling gear in shopping trolleys, on skateboards and anything with wheels, around Sunderland council estates.

The Bunker grew out of the formation of the Sunderland Musicians’ Collective (SMC) in September 1980. This was all driven by necessity. We were helped by Andy Gibson who called for bands to meet to form a “musicians’ collective”. After many, many meetings in pubs and community centres, the SMC was born. In 1981, the council gave the SMC the lease on a room situated above the council’s community garage at 60 Borough Road, Hendon.

It was an empty room, which suited us. The SMC formed a committee and put on benefit gigs at the local the Art College and various pubs and clubs to raise funds for materials. The local media became interested in a bunch of scruffy punks and other misfits who could organise themselves into a DIY collective. The Sunderland Echo and Tyne Tees Television did articles on the SMC, so when the council’s Environmental Health department said they were closing us down for “excess noise”, we had already had positive media exposure. When we went to meet with local councillors, we were organised, and we put our case to the Education department. Our plan was to try and encourage other community groups to share the building, and the council offered us the upstairs of a Victorian school.

Where were these new premises situated, and what did they comprise of in the early days?

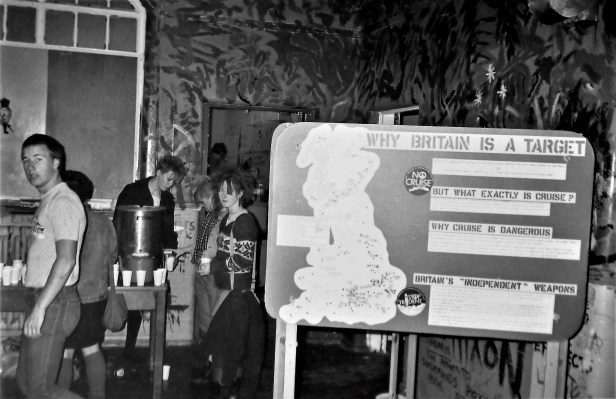

“The Bunker”, at Green Terrace School, was situated in Sunderland town centre, right next door to the multi-million-pound leisure centre. It was massive compared to 60 Borough Road. It comprised four large classrooms centred around a main hall, with two smaller classrooms on the upper floors. We rented classrooms to various groups, including Ford and Pennywell weightlifters, Sunderland Youth CND and Springboard Drama Group. The main office would be the base for the Sunderland Musicians’ Collective and what would become the Bunker Collective.

Can you confirm the origin of the name? Was it intended to evoke the idea of ‘punks under siege’, or be a reference to a nuclear shelter, or something else?

We painted the walls of the main hall in camouflage style, and got some fishing nets from the docks. Then someone said: “it looks like a bunker.” The name stuck.

Can you describe some of the first gigs and events at the venue? How were things at the beginning?

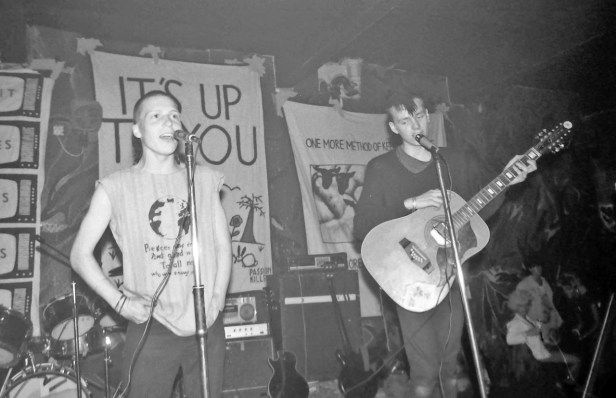

The first gig was on 4 September 1982, and featured local bands only: Side Effects, Patrick, and Tommy Hair’s dub war disco. The first anarcho-punk band to play the Bunker was Dirt in October 1982 followed by the Poison Girls in December. The atmosphere at these gigs was amazing. It changed a lot of punks in Sunderland. We had already seen Crass and a few other anarcho-punk bands, but for young punks who couldn’t get into gigs, this was their first chance of seeing these bands live. So it was life-changing for young people to feel safe at a gig, to hear the music that mattered to them and be able to be part of an event.

We painted the walls of the main hall in camouflage style, and got some fishing nets from the docks. Then someone said: “it looks like a bunker.” The name stuck.

People would stay behind at the end of gigs to help out with the tidying, humping the groups’ gear back into vans, and most importantly meeting the bands. None of the anarcho-punk bands were like pop stars. They were different, they always had time for the fans. With no interference from adults, it must have seemed “too good to be true” to some – and our ranks swelled. After four months of gigs and events, the Bunker committee had grown. More people were taking part in the general running of the building, not just the hardcore group of us who had been there from the beginning. At the second Bunker AGM on 15 November 1982, 34 people turned up, 15 of the attendees were girls (only one girl had been involved at the first AGM in January). We always wanted a large and diverse group of people to run the project; the committee wasn’t just punks either, it was made up of all kinds of musical tastes.

Was there an immediate ‘audience’ for The Bunker, as word spread? From how far afield did people come from?

Punk gigs had always been well attended in Sunderland, so we had no problem in getting the locals in. Russell Dunbar, Michael Dunbar and Raf Mulla had started Acts of Defiance fanzine around about the same time as the SMC was founded. They advertised the formation of the Bunker and its goings on, they published gig reviews, newsletters and details of forthcoming gigs. Raf and Russ were both involved in the Bunker from the early days. This helped spread the word, and with the national fanzine scene, and soaped stamps, the word went national. Anarcho-punk led to more friendly relations between our neighbours from Newcastle and Tyneside. Before it was still that stupid football tribalism that stood in the way of our getting to know people. They had the Garage in Newcastle, and then the Station in Gateshead, and we all would support each other’s venue. Punters started turning up from all over the country and, by the time we had established the Stockton Road Bunker, punks were moving up to Sunderland to live.

Was the Bunker an ‘anarchist’ or an ‘anarcho-punk’ venue? How would you describe the principles on which it was run?

The Bunker was non-profit, run on co-operative rules and totally voluntary. It had the main Bunker Collective committee who ran the venue and smaller sub committees who ran their own rooms. When we started the Bunker, it was for local bands to have a venue and a place to practice. It was a intentionally varied platform, and all kinds of music graced the Bunker. People associated the Bunker with anarcho-punk, and it was a large part of the early Bunker’s identity and its principles. But as well as the larger anarcho-punk gigs, the early eighties’ Sunderland music scene was made up of old school punk, new wave, art school bands, new romantics and Oi bands.

Did the people running The Bunker feel a close affinity with other DIY venues elsewhere in the country, or was The Bunker’s identity unique?

We had close connections with the people running the Gateshead Musicians’ Collective whose venue was The Station based in Gateshead about half an hour away from us. They had a similar timeline and ethos to the Sunderland Musicians’ Collective and, although close together, both venues thrived. We tried not to clash gig dates with each other, and had lots of interaction between the two collectives. The Bunker was fairly distinctive as a space; the building, particularly Stockton Road, was used by lots of other young people, not just musicians, over the years: there was a café, a DIY clothes shop, weight lifters, artists as well as practice rooms and the venue.

How were things run? Did the place make enough money to fund itself?

Everyone on the committee was allocated a job for the day-to-day running of the Bunker; especially when we were trying to get the venue ready for gigs. You were accountable for your task. If you said you would open up for bands to practice, you had to do it, or the whole thing would collapse. But it did work. We wanted it to succeed. Funding was always a challenge. The early days of the SMC and the Bunker can be best described as always having to be on the scrounge, and endless letter writing (no such thing as email back then). We wrote to funding bodies, local authorities and anyone who we thought had money. Some income was raised from these sources, but the vast majority of these organisations said that they had “no funds available.” We used all the rejection letters to decorate the Bunker office in Stockton Road.

You were accountable for your task. If you said you would open up for bands to practice, you had to do it, or the whole thing would collapse

The venue became fairly self-sufficient. The best form of revenue at the time was the anarcho-punk gigs, that were very well attended. Bands were happy to play for the door money, after we’d covered PA expenses and other costs. In the beginning, these helped us to pay the rates and utilities and kept us going. We also raised a lot of money for other causes via benefit gigs, the striking miners, animal rights – all the usual anarcho stuff.

The Bunker was run as a collective by volunteers, The Sunderland Youth Employment Project had a 9-to-5 office in the building. They were funded by the local council and helped us with sourcing grants to help with the day to day running of the project. They were a great bunch of people who put a huge amount of effort into helping get any one’s ideas off the ground. To us at the time they seemed like old hippies; in reality, they weren’t much older than us! Andy Gibson was again a hugely important figure. He was the driving force behind SYEP who has now sadly passed away. His input and enthusiasm in The Bunker collective was immense.

What were the connections between what was happening at The Bunker and other things in the local punk scene (bands, labels, fanzines, demonstrations)?

The Bunker wasn’t just an anarcho-punk project. Some of the collective’s members had no interest in the anarcho side of things, although many of the people involved in the collective could loosely have been called “punk”. Just like many other places across the UK, the punk scene in Sunderland in the early eighties was pretty diverse. Skinhead, ‘77 style and “UK82” type bands all practiced at the Bunker. I’m not saying we always got on together, and the musicians’ collective meetings could be pretty lively. But we did try to engage with all the punks. I suppose throughout the collective’s early years, the anarcho-punks shouted the loudest, and we tried to keep the gigs and ethos surrounding the Bunker’s ideals as anarcho as possible. Loads of bands wanted to play the venue, but we wouldn’t entertain them if they didn’t fit our anarcho ideals. Of course, this led to some degree of conflict, with us often getting called a “clique.” People were probably right, but some of us had very high ideals at the time in the way we saw how the venue should be run.

The Bunker did have a good reputation as an “anarcho punk venue”, but others involved in the collective weren’t always happy with this. I think a lot of the association with anarcho-punk comes from the Bunker’s connections with Acts of Defiance fanzine. Many of the bands who played at the Bunker will have made initial contact with us by either writing to or being included in the fanzine. Several collective members were well known within the anarcho-punk scene which made it easy for us to get that type of band up to Sunderland to play. The building and gigs were a hub for the exchange of leaflets, fanzines and ideas relating to what was going on in the wider anarcho-punk scene. People travelled from all over the country to the gigs. It wasn’t unusual for us to have twenty or more people sleeping on the floor in our flats after gigs!

How did the local council (and local law enforcement) respond to the existence of the place?

We had that indispensable help in the beginning from Andy Gibson from the Ford and Pennywell Youth Project, and Mick Catmull from the Community Arts Project in Hendon. Without these youth workers agreeing to be our “responsible adults”, we would never have got off the ground. They helped us to be more organised. Andy would come to licensing meetings with the council and the police, but let us do the talking. The meetings with the police were, on the surface at least, all about music and entertainment licences. But they seemed very interested in what was going on inside the building. After one young copper wandered in during the day, only to be confronted by anti-government, anti-state and anti-police grafftti, posters and banners, this information was, of course, reported.

The police would try to come to gigs we always refused entry to them, explaining there was “nothing to see, just a load of pogoing punks and anyway it was a private members’ club and they weren’t members.” They were always OK about it. There was enough trouble in Sunderland for them to deal with without bothering us. There were two train of thought about this: either the police in Sunderland didn’t care about us, and just let us get on with it; or, the existence of the Bunker meant the police knew were all the political trouble makers in Sunderland could be found. When the police raided a flat in Park Place, where two of the punk activists involved in the Bunker were living, on the pretext of investigating a burglary, it was like something out of the Young Ones.

Did the place suffer from the usual DIY premises problems: violent interlopers, vandalism, too few volunteers, and the like?

In the early days of the Bunker we had very little trouble. At the Green Terrace Bunker the Newt brothers, Harry and Steve, were employed to keep order. Some of us knew them from Doxford Park. They were nice guys, but psychos, and there was also a massive squad of members on duty at gigs ready to deal with any trouble. The “Station Skins”, who were named after the bus station opposite the Bunker, could be a nuisance. They would sometimes attack punks leaving the venue, but never dared to come to the Bunker to cause trouble. I can only think of a handful of incidents, and nothing serious with the punters.

The Green Terrace Bunker was once attacked by bouncers sent from one of the local pubs by a night club owner who said we were “putting him out of business.” Someone let us know about the plan, and when they turned up mob-handed and started putting the windows out, we were ready and chased them off. There was more trouble at the Stockton Road Bunker. The popularity of gigs was growing, and the larger venue brought its own set of problems.

The local council was willing to give a bunch of punks the keys to a Victorian school and a run-down Arts Centre without asking that many questions

No matter how many times you said “No glue, no glass bottles,” people would still bring glass, and want to get in for nothing. By now, the original members were in their twenties and were dealing with a much younger crowd. The police took exception to people drinking on the street outside the premises on Stockton Rood itself, so when you asked people to come inside (leaving their bottles of beer outside), you could be on the receiving end of a “fuck off!”. Trying to explain that we could get shut down just didn’t get through to some of the so-called anarcho-punks.

What led to the relocation to new premises? Was it a step forward in itself?

In February 1983, the Leisure Centre’s roof was blown off in a huge storm, and of course the massive debris landed on the Green Terrace Bunker’s roof just next door. This left us with a ceiling like a colander. Rain water poured in, blew the electrics and flooded the building. The area was up for redevelopment, and we knew that eventually we would have to move. We had already been offered alternative buildings, and we settled on the Stockton Road site. It had been an old bakery before turning into the Celofrith Art Centre. The building was even bigger than Green Terrace. It had a larger main hall with loads of smaller rooms spread across three levels.

The new premises needed lots of work doing to it. We decided that we would keep the Bunker name, as it was already well established. Sunderland Youth Employment Project was formed to support local youngsters trying to find work in the area and to assist with the running of the new, and bigger, Bunker. The new premises were a step forward for the project, and we expanded operations: starting up printing and badge making workshops, housing cooperatives, and “Persons Unknown”, Sunderland’s first pirate radio station.

What in the end led to closure of The Bunker in its original guise? Did it feel like the project had passed its peak, or was there unrealised potential in the idea?

The Bunker still exists at 29 Stockton Road today, although now run as a “social enterprise business”. If you’re taking about the Bunker as a venue it effectively ended not long after Conflict played with Steve Ignorant in 1987. The local authority revoked the entertainment licence after asking for the gig not to go ahead due to the carry on surrounding Conflict’s notorious ‘Gathering of the 5000’ gig in Brixton that April. That “last” Bunker gig was organised by people who took over after we had stood down. I don’t hold anything against them putting the gig on though. I would have done it myself!

The atmosphere had already begun to evolve before that. Towards the end of 1985 change was in the air, many of the original collective members had moved on. I think people were getting tired of the whole anarcho-punk thing. Attendance at gigs was dropping off, and some collective members were wanting to start putting the more “UK82” type stuff on: bands like Peter & the Test Tube Babies and The Exploited. I just felt that that all went against the original ethos of what the Bunker stood for so, after three years of being involved in organising gigs there, my time was up. I left it for others to continue.

I don’t think there’s any “unrealised potential” as such. As a collective group of young people, we achieved a great deal. The Bunker is still a fantastic resource for up-and-coming musicians and some great bands have come out of Sunderland, in part helped by the Bunker. There is a DIY café and record shop within the Bunker: Pop Recs Ltd. Dave Harper and Michael McKnight who run it have been a massive help to us in organising “The Bunker 35” weekend. We also use their space to puts gigs on still which is really good for us to be able to do stuff in the original building. We can’t thank them enough for their help.

Have there been previous efforts to record and celebrate the experience of The Bunker (online and through events)?

In 2006, Paul Maven (AKA Booga Benson) built a web site called “the Bunker Archive” for his Photography MA. He got a lot of interest, so he continued after he received his Master’s degree. We arranged a couple of benefit gigs to fund the site, at The Black Bull in Sunderland. That was would be the last time that many of us would see Andy Gibson. Billy Bragg supported the site with donations, but through illness and lack of funds Booga was not able to keep the site going.

What were the triggers that brought together the “No Glue, No Glass Bottles” team now?

The “Bunker Group 35” is simply a reflection of the fact that it’s the thirty-fifth anniversary since the Bunker collective’s very first gig at the original Bunker (at Green Terrace School). “No Glue, No Glass Bottles” was the slogan on most of the Bunker posters. Of the original committee, Alan and Jill Christie, Marnie and Andy Hardcore have remained close friends over the years since the Bunker’s heyday. Between us we have an extensive archive of ephemera from back then: we knew others also had lots of unseen photos and literature from back in the day, so we started to collect and get permission to use this archive material.

At first, we didn’t know what we wanted to do, or how best to go about it, but we just felt we needed to do something to commemorate something that was a large part of our lives. Over the years I’ve seen opportunities missed to commemorate important events from within the underground and alternative scenes. The Battle of The Bean Field (the police assault on the Stonehenge convoy on 1 June 1985) springs to mind as something I think people missed out on commemorating on its thirtieth anniversary. I know a few people did mark the moment, but I feel it could have been a lot bigger event. We’re all in our fifties now. It just felt right to do something to celebrate the history of the Bunker’s early years before we’re too old to do it!

What events are being planned to do that?

The initial events will be on the 8-9 September 2017, this will include a photographic exhibition, documenting a history of the Sunderland Musicians’ Collective and the Bunker, alongside a display of original Bunker fanzines, tickets and artwork. There will also be screenings of the Bunker video, which was made in 1982, the Sparks youth programme from the BBC, and local television news clips about the Bunker. Reproduction gig posters will also be on sale. There will be live music from Early Maze on Friday 8 September and Anti System, Andy T and Prolefeed on Saturday 9 September. The exhibition will then be on display at Pop Recs for eight weeks, and we are hoping for the exhibition to tour around the north-east in 2018.

Have you found a positive response so far to your plans? What sort of interest and engagement are you seeing?

The response so far has been overwhelming. The archive material – especially photographs that we have been given permission to use in the exhibition – has amazed us. It’s so good being able to get bands that played at the Bunker back in the 1980s back up to the same building to play again. Andy T and Anti-System haven’t been back to Sunderland since the Bunker venue closed. Although much smaller than in the 1980s, there is still a thriving DIY punk scene in Sunderland. Quite a few people who over different times were involved in the Bunker collective are still involved in putting gigs on and releasing records. The DIY punk scene in Sunderland is better now than it has been for many years, and I’m sure there’s still plenty of life left in yet.

What would you hope the “legacy” of The Bunker might be?

The legacy of the Bunker continues to this day. It might not be the same set-up we had in the early days, but it is the same ethos that drives it now: the love of music. The Bunker today is a Community Interest Trust and owned and run by people who took on the building after us. It still provides practice rooms, recording studios, runs lots of different music workshops and hosts a rock school in the holidays. It has been a hard few years for the Bunker, and it has been under threat of closure on-and-off due to funding shortfalls. It would be a massive loss for the local community if it were to shut.

Could a new generation of young kids create something akin to The Bunker today?

Nothing is impossible, but we were lucky to be born into an age where a local council was willing to give a bunch of punks the keys to a Victorian school and a run-down Arts Centre without asking that many questions. DIY is certainly still alive and kicking in Sunderland with more bands than ever playing and setting up their own do-it-yourself gigs.

Great read! Looking forward to next weekend. All the hard work Christie and Andy and others too numerous to mention have done should be recognised.